Abstract

There’s a lot of research built around the field of sleep, such as the role it plays for our body from a biological standpoint (i.e. regulating metabolism, flushing out toxin build-up in the brain, consolidating learning and memory). However, one essential part of sleep is not discussed as widely as it should be: dreams. Dreams research is relatively new in the world of science, but has potential to expand exponentially by harnessing virtual reality (VR) technologies and other devices providing external stimuli. Dream engineering, such as targeted dream direction and sleep manipulation, can be applied to engineering better sleep, clinical usage in terms of psychotherapy, and expand upon technologies involving the brain.

How do you feel about sleep?

Sleeping just might be everyone’s obvious favorite hobby: it definitely is one of mine. Especially as college students, we look forward to the end of the day when we get to jump in bed and snuggle inside our (hopefully) clean sheets– seeing sleep as some sort of reward for a long day. Some of us go to bed with the thoughts of, “I’ll just finish that in the morning,” or the alternative: “thank heavens that I’m finally done with that godforsaken assignment. I haven’t slept in 28 hours.” After the lights turn off and our heads hit the pillow, we slowly enter a different world — the world of dreams.

While we are all familiar with the experience of dreaming, few may know that dreams have become a recent venture in the world of science. The first recorded discovery of REM sleep was in 1953 and experiments to see if dream content may be altered by telepathic communication came shortly after in 1969. Humans, as the curious and innovative creatures we are, constantly seek ways to explore every aspect of human life — and dreams are no exception. Engineering and manipulating dreams seem like such a pop science-fiction concept and out of touch with reality (e.g. the 2010 blockbuster Inception, starring Leonardo DiCaprio), but we’re getting closer and closer to making it a reality. Dreams give us a vast wonderland of creative potential, and what lies in the untapped human subconscious could reveal things that we can’t even imagine. But can we tamper with the intangible?

First Things First: What Exactly is a Dream and Why Do We Do It?

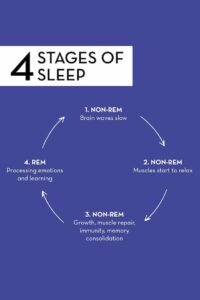

Everybody dreams. Dreams are a universal part of human experience, often considered a subjective experience generated by the mind and brain while cut off from the physical body and the exterior environment [1]. In a typical night, a person goes through four to six sleep cycles, and within a sleep cycle, there are four stages of sleep. As seen on Figure 1, the first three stages are NREM (non-REM), and the fourth being REM (rapid eye movement) [2]. When we enter REM, it triggers delusional, disordered hallucinations, which we know as dreams. The role of sleep is widely known in science (it regulates our metabolism, blood pressure, and brain function), but we don’t know why we dream. However, there are numerous popular theories as to why we do.

Figure 1. The four stages of sleep.

One approach is purely psychoanalytical: outlined in Freud’s “The Interpretation of Dreams,” he suggested that dreams — which are partially drawn from stimuli and experiences in the waking world — are a roadmap to the unconscious, reflecting our deepest desires and wishes [2]. However, the activation-synthesis model (also called the protoconsciousness theory) proposed by Harvard psychiatrists J. Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley in 1977 has a much more neurobiological take. The theory stands that “dreams are your brain’s attempts to make sense of random patterns of firing neurons while you slumber” and curating specific dream content [3]. Yet another theory about dreams is that they help analyze and consolidate memories, a process where recent and learned experiences are converted into long-term storage. There’s also the more primitive biological threat simulation theory, which holds that “dreaming enables the brain to rehearse new survival strategies without having to defend against an actual threat,” as a byproduct of our evolution. And in regards to dream content, there is the continuity hypothesis: dream content is psychologically meaningful in that it reflects the dreamer’s current thoughts, concerns and salient experiences [3]. However, it is important to note that none of these theories have been proven nor do they have significant credibility over another given the ambiguous nature of dreams.

…So Why Are We Engineering Something We Don’t Even Know Much About?

That’s true. Discovery of electroencephalograms (EEGs) in the second half of the 20th century, a test which detects abnormalities in your brain waves, launched the post-Freudian era of dream research. Dream science is a pretty modern concept. However, 21st century scientists aren’t the first to experiment with dreams. Ancient Egyptians have been known to fast to induce vivid dreams for enlightenment, as well as artists and philosophers who have been experimenting for centuries with hashish, opium, and other drugs for the same purpose. Documentation dating back to 350 BC in the early writings of Aristotle mention descriptions of lucid dreaming. In the 1800s, Thomas Edison trained himself to recognize when he was about to fall asleep so he could solve problems he had trouble with when he was awake [3]. So it’s safe to say that it’s been in the works for a while, just not measured and studied extensively.

This field of study is interesting because the brain is anything but passive during sleep. Brain activity of the sleeping mind poses questions such as how human subconsciousness can be altered in response to external stimuli, and to explore the untapped creativity that lies in the subconscious. Today, scientists aim to use dream engineering to explore the potential for creating specific cognitive content in dreams. This includes technologies enhancing specific memories and dampening others during sleep, techniques for forming new habits and associations, and changing the actual subject matter and substance of dreams [1]. Therefore, scientists have been exploring directed reactivation in sleep (where patterns of neural activity expressed during perceptual experience are re-expressed at a later time), science of lucid dreaming, memory replay, dream influencing techniques, and much more on the dreaming phenomena [4]. Applications cover a wide range, from clinical usage in psychotherapy to recreational uses such as stirring creativity. Dream engineers use a variety of technologies to monitor and attempt to alter people’s dream experiences, especially using sensory stimulation. Although it is still in a very experimental stage, one of the more popular methods is through HCI (human-computer interaction) technologies.

Virtual Reality Technology and Noninvasive Brain Stimulation Can Be Used to Manipulate Dreams. (Spoiler: It’s Through Lucid Dreaming.)

Scientists who study dream engineering believe that “the brain is genetically endowed with an innate virtual reality generator that — through experience-dependent plasticity — becomes a generative predictive model of the world” [6]. Hence, components of virtual reality (VR) can be translated to dream engineering. VR by scientific definition is a computer-generated environment with scenes and objects that appear to be real, making the user feel that they are immersed in their surroundings [7]. A popular example of this is the Oculus VR, where you put on the headset and you’re immediately transported to a different world. Dreams, by definition, are virtual as their “subjective attributes are fabricated internally” with the psychology of imagination and subjective processing coming into play [6]. That being said, there are many parallels between virtual reality and a dreaming state; by using a VR device, you are essentially putting yourself into a brain state that is similar to the REM brain state, especially during lucid dreaming.

A lucid dream is a dream in which “the dreamer is aware that they are dreaming while the dream is still happening” and is a surprisingly common experience with 55% of adults reporting to have experienced it at least once in their lives [7]. In a lucid dream, you may be able to manipulate your own actions in the reality that you have created for yourself. This phenomenon can occur either during REM or hypnagogia. Hypnagogia is the “transitional state of consciousness between wakefulness and sleep,” where it’s common to “experience involuntary and imagined experiences.” It happens right before you fall asleep, and your sense of reality transitions from the real world to the dream world, leading to a distorted perception of space and time. Sleep paralysis, hallucinations, lucid dreaming, and body jerks are common experiences at this point [8]. When you’re dozing off in class and jerk awake to the feeling of free-falling off a building, you’re in a stage of hypnagogia. Researchers wonder if people in the state of hypnagogia could be influenced by external stimuli to generate certain dream content.

To test this theory, researchers from the MIT Media Lab’s Fluid Interfaces group — a group dedicated to creating systems and experiences for cognitive enhancement influenced by Psychology and Neuroscience — invented Dormio, a wearable sleep-tracking sensor device that aims to direct dream content to augment human creativity during the state of hypnagogia shown in Figure 2. These researchers realized that current human-computer interaction (HCI) research overlooks an opportunity to create interaction between the machine and the human body during dreams and drowsiness. Introducing a novel method called “Targeted Dream Incubation” (TDI), this protocol is “implemented through an app in conjunction with a wearable sleep-tracking sensor device,” which “not only helps record dream reports, but also guides dreams toward particular themes by repeating targeted information at sleep onset, thereby enabling incorporation of this information into dream content” [9]. This serves as tools for controlled experimentation in dream study, widening avenues for research into how dreams impact emotion, creativity, memory, and beyond.

Figure 2. Dormio, created by MIT scientists in 2021, is a wearable sleep-tracking sensor device that may allow you to manipulate your own dreams. It is the first-ever interactive interface for sleep.

Dormio can “influence, extract information from, and extend hypnagogic microdreams for the first time,” meaning it can literally shape your dreams [10]. During testing, the participants wore Dormio which tracked their muscle tone, skin conductance (continuous variation in the electrical characteristics of the skin), and heart rate changes. When the data showed they hit hypnagogia, they were gently prodded towards a more wakeful state and played an audio message to attempt to influence their dream content. Results revealed that the subjects had dreamt about the themes chosen by experimenters prior to sleep, bolstering evidence that Dormio can be used to augment dreams [9].

Dream Engineering Can Be Useful in a Wide Array of Fields.

But why do we care about this in the long run? Manipulating dream direction could be used for clinical purposes, such as psychotherapy for PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) sufferers. Nightmares and night terrors are a common experience for those with PTSD, and technologies like Dormio could help them cope by having them experience traumatic events and inner conflicts through anxiety-free images during the state of hypnagogia [10]. Patients could use lucid dreaming tactics to confront a situation of interest, and to try and understand what kind of thoughts and concerns they may represent in their consciousness. Although not yet backed by solid scientific research, people may be able to shape opportunities to work with the psychological content of their dreams.

In addition, we can actually engineer better sleep by manipulating dreams through various technologies applying stimuli to our senses: touch, sight, hearing, and smell. Dormio uses aural stimuli, while other technologies such as bone conductors, light stimulation masks, thermal sheets, olfactometers, Electrical Muscle Stimulation, and more. There has been headway in making machine-learning algorithms for sleep staging using these wearable technologies, radio signals, or EEGs; a few examples are included in Figure 3. These devices implement several techniques to improve sleep hygiene, enhance memory and learning, and augment creativity. One method is called Targeted Reactivation (TLR), which involves the pairing of external cues with task performance to improve certain performances, such as better retention of memory. Another method is called Dream Direction (DD), which is pretty self-explanatory: directing the content of dreams. There is also Rhythmic Entrainment (RE), which is a form of music therapy that utilizes auditory rhythms to stimulate the central nervous system and improve brain function [1].

Controlling a brain-computer interface (BCI) device is also possible during a lucid dream, meaning lucid dreamers “may be able to send real-time signals from sleep to the external world” [12]. Remington Mallett, a postdoctoral researcher at Northwestern University focusing on memory, sleep, and dreams, showed that using an Emotiv EPOC+ headset (a consumer BCI), a lucid dreamer was able to control a moving block on a computer screen as instructed, while asleep. Although preliminary, the results from this study suggest that BCI can be controlled from sleep and offer directions for future dream research and two-way communication. This could open up opportunities for advanced neuroprosthetics to help disabled patients, for example, in re-learning how to send motor commands to a limb or spine [1].

Figure 3. Dream engineering requires lots of technologies in play, with technologies highlighted in teal to moderate, and technologies in purple to attempt to modulate. Not all of these are used simultaneously, but it gives a good idea of what technologies can be involved in dream engineering.

This is Great and All, but is Dream Engineering Ethical?

At first glance, engineering dreams and sleep research sounds cool, like something straight out of a sci-fi movie. However, once it gets down to the nitty gritty, there are certain aspects that are questionable. The ideas of mind-control and inception, such as “introducing certain ideas into an individual’s memory without their conscious awareness” have raised public concerns regarding subliminal messaging [1]. This has become even a bigger concern as there is emerging evidence for hypnopaedia, which is a scientific term for sleep-learning (forming new memories while asleep). Even though positive associations and habits can be formed via sleep-learning (e.g. reduction in smoking), there may also be negative consequences (i.e. creating political bias) [1]. When asleep, individuals are vulnerable to potentially nefarious influences and the public may not feel very keen on this possibility.

Concerns also exist about the detrimental effects on the individual’s health, as alteration of the architecture of sleep manipulates a natural process in human routine. Regulation of the body and other health benefits of sleeping and dreaming may be weakened in the process. And although speculative, the potential for selling data about the dreaming self raises concerns; this is especially relevant in this day and age [4]. Therefore, those involved in sleep research and dream engineering should adhere to guidelines and should be diligent in the way they build future technology, especially being sure that it is supplemental in nature rather than utilizing for substitution. However, this is also a bit difficult as there are no strict, written guidelines to adhere to given its recency in science.

So, What Does the Future Hold for Dream Engineering?

Dream engineering is a frontier of scientific investigation: this means even though we don’t know much about it yet, the potential in this field is vast. Technologies such as Dormio unlock the next step for dream research and engineering, as they allow scientists to interact with their study participants during sleep, which was not possible before. As research on lucid dreaming and the development of dream incubation technology progresses, controlled experimentation on dreams is now becoming evermore possible. This can be used to engineer better sleep, potentially create better neurotechnology, advance neuroscientific studies of the brain–mind system’s activities during sleep, and explore psychotherapeutic applications of dreams [13].

References

| [1] | M. Carr, A. Haar, J. Amores, P. Lopes, G. Bernal, T. Vega, O. Rosello, A. Jain, P. Maes, “Dream engineering: Simulating worlds through sensory stimulation,” Consciousness and Cognition, vol. 86, August 2020. [Online]. Available: ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/ [Accessed Mar. 20, 2022] |

| [2] | E. Suni, N. Vyas, “Stages of Sleep,” March 2022. [Online]. Available: Sleep Foundation, https://www.sleepfoundation.org/ [Accessed Mar. 20, 2022] |

| [3] | A. Orlando, “Why Do We Dream? Science Offers a Few Possibilities,” December 2020. [Online]. Available: Discover, https://www.discovermagazine.com/ [Accessed Mar. 20, 2022] |

| [4] | A. Haar, P. Maes, M. Carr, “A Dream Engineering Ethic,” November 2020. Available: Infinite Zero, https://00.pubpub.org/ [Accessed Mar. 21, 2022] |

| [5] | C. Offord, “Scientists Engineer Dreams to Understand the Sleeping Brain,” December 2020. [Online.] Available: The Scientist, https://www.the-scientist.com/ [Accessed Mar. 23, 2022] |

| [6] | A. Hobson, C. Hong, K. Friston, “Virtual reality and consciousness inference in dreaming,” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ [Accessed Mar. 27, 2022] |

| [7] | D. Apsy, P. Delfabbro, M. Proeve, P. Mohr, “Reality testing and the mnemonic induction of lucid dreams: Findings from the national Australian lucid dream induction study,” Dreaming, vol. 27, 206-231, September 2017. [Online]. Available: ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ [Accessed Mar. 27, 2022] |

| [8] | “What Is Hypnagogia, the State Between Wakefulness and Sleep?” October 2021. [Online]. Available: Healthline, https://www.healthline.com/ [Accessed Mar. 27, 2022] |

| [9] | “Dormio: Interfacing with Dreams,” April 2018. Available: MIT Media Lab, https://www.media.mit.edu/ [Accessed Mar. 29, 2022] |

| [10] | R. McCall, “Scientists at MIT Have Created A Machine That Can Literally Shape The Content Of Your Dreams,” April 2018. [Online.] Available: IFLS, https://www.iflscience.com/ [Accessed Mar. 29, 2022] |

| [11] | Noreika, V., Windt, J.M., Kern, M. et al. Modulating dream experience: Noninvasive brain stimulation over the sensorimotor cortex reduces dream movement. April 2020. Available: https://www.nature.com/ [Accessed Mar. 29, 2022] |

| [12] | R. Mallett, “A pilot investigation into brain-computer interface use during a lucid dream,” International Journal of Dream Research, vol. 13, p. 62-69, March 2020. [Online.] Available: https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/ [Accessed Apr. 1, 2022] |

| [13] | K. Bulkeley, “The future of dream science,” Special Issue: Unlocking the Unconscious: Exploring the Undiscovered Self, vol. 1406, p. 68-70, January 2018. [Online.] Available: The New York Academy of Sciences, https://nyaspubs-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.libproxy2.usc.edu/ [Accessed April 1, 2022] |