The medieval battlefield was dominated by large artillery weapons, and among these the trebuchet was king. This massive weapon was eventually capable of throwing massive boulders over 250 meters, but it did not start that way. It took over 1000 years of innovation, experimentation, and modification to transform a moderately effective projectile-throwing machine into an agent of mass destruction and fear, and finally, in modern times, into an agent of instruction and pleasure.

Introduction

Artillery has been the centerpiece of many armies over the centuries because of the massive amounts of destruction, fear, and uncertainty it has caused in enemy camps. This aspect of warfare has made tremendous advancements throughout history, with current artillery weapons having the capability of sending projectiles past the horizon and landing within a few feet of their intended targets. These super weapons are the result of over two millennia of trial and error that began with the development of the trebuchet.

Predecessors

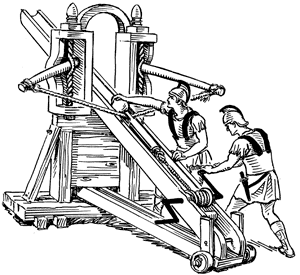

Two of the major predecessors of the trebuchet were the ballista (Fig. 1) and the catapult [1]. The ballista “was a type of large crossbow” that worked very much like a bow, using the tension created by pulling back a string or rope along with a trigger mechanism to fire spear-like ammunition [2]. The ballista worked well against troops and cavalry, but had no effect upon walls and structures [2]. The ballista eventually gave way to the catapult [3].

The catapult consisted of a solid base with a pivoting arm that would be pulled down and locked into place [1]. Once the arm was in place, the projectile would be loaded into a cup at the end of the arm. The force that the catapult needed to launch the projectile came from the manipulation of twisted ropes [3]. The catapult operator would twist ropes that surrounded the pivoting arm, causing immense tension. When the catapult was released, the ropes would twist back into shape and swing the pivoting arm upward until it reached a vertical position and hit a cushioned pad. The pivoting arm would then stop and the projectile would be flung forward. In order to change the trajectory of the projectile, the operators had the option of either “angling the whole machine or changing the angle of the crossbar” [1]. A powerful catapult had the capability to launch a 27-kilogram stone, but had little effect on walls or fortified buildings located over 160 meters away [3].

The Trebuchet

The trebuchet made improvements upon both of these weapons, able to launch stones that weighed hundreds of kilograms farther and more accurately than either the ballista or the catapult. With this power, a trebuchet could destroy even fortified walls quite easily and quickly replaced catapults as the weapon of choice on the medieval battlefield.

The trebuchet consists of a long beam placed off center on a pivot on a large base that would support the entire apparatus (Fig. 2). The longer end of the beam would hold the projectile while the shorter end would hold a counter weight [2]. The counterweight is usually very heavy and provides the mechanical force to fire. In order to maximize the distance the projectile flies, the trebuchet needs to have a relatively long throwing arm compared to the counterweight’s arm, and a relatively large weight relative to the object being thrown. The proper ratio for the throwing arm to the short arm is approximately 4 to 1, while the proper ratio for the counterweight to the projectile is approximately 100 to 1 [4].

One of the most important components of the trebuchet is the sling, which greatly increases the range of the weapon by simply extending the length of the throwing arm [5]. Not only does the sling add firing distance to the trebuchet, it gives the crew manning the trebuchet the ability to aim. Before the addition of the sling, the crew had to move the entire trebuchet to change the direction of the trajectory. With the sling in place, the crew just has to change the angle of the sling and the projectile will be aimed at its new target.

The Evolution of the Trebuchet

The earliest trebuchets were “traction trebuchets [which] were invented in China in the 5th – 3rd centuries B.C.E.” [6]. Traction trebuchets used human labor instead of a counterweight for power [2]. The Chinese needed so much power for the trebuchet that they had up to 250 solders pulling on ropes to operate the machine [6]. This machine could throw stones up to 100 meters, but was not very accurate, given the inherent inconsistency in using true manpower.

The addition of a fixed counterweight was a major advancement in trebuchet technology. This counterweight was affixed to the end of the shorter arm and, without the need for ropes and people to pull the machine, space was available for lengthening the sling, which allowed the projectile to go even farther [3]. Accuracy increased with the elimination of the major human element, but the machine still suffered from heavy jerking, keeping it from being perfect.

The fixed counterweight eventually gave way to a hinged counterweight (Fig. 3). The hinge greatly increased the efficiency of the motion involving the counterweight, causing more power to be delivered to the projectile. The hinge also helped to slow down the system when it reached the bottom. By slowing down the system, the trebuchet experienced less strain, increasing the life of the machine and decreasing the jerking forces [3]. Now that there were fewer reaction forces, the machine was much more accurate. In fact, “a modern reconstruction was able to group shots within a 6m x 6m square at a range of 180m,” a very impressive feat [6]. The power delivered to a wall from a device like this could be incredibly devastating. Also, the newfound stability meant that the trebuchet did not have to be repositioned after every shot, so firing time improved to about twice per hour [6].

One of the final improvements to reach the trebuchet was the “propped counterweight” [3]. The propped counterweight was very similar to the hinged counterweight, except the weight was forced to make an angle with the arm instead of hanging straight down. This created an increase in falling distance and centrifugal force, both of which contributed to greater power. These improvements helped the trebuchet maintain dominance on the battlefield.

The Trebuchet in Action

Medieval battlefields consisted mainly of sieges to fortified cities by some hostile force. Actual hand-to-hand combat was quite rare and usually only occurred during midnight counterattacks by the besieged or when the walls of the city were finally breached. Consequently, trebuchets dominated the battlefield with their ability to fling 300 lb. stones up to 275 meters, obliterating walls in their path[7]. In order to maximize their chance of winning, both the attackers and defenders employed trebuchets to help their cause. However, since the trebuchet is much easier to aim at a large stationary target than small mobile targets, it was usually much more effective for the side laying siege[1].

Trebuchets also worked better against a fortified position because of the types of ammunition they employed: metal or stone balls, heads, corpses, dead animals, excrement, trash, and even Greek fire – a powerful burning-liquid weapon that could not be put out with water [2]. Most of these items were meant not to destroy walls, but to humiliate the enemy, taint their water supplies, and spread death and disease. One of the worst cases of such early chemical warfare came in the 14th century when Mongols fired corpses that contained the Black Death into the city of Kaffa. Kaffa was a port city, so the disease soon spread across the Mediterranean and into European ports [3].

Conclusion

Although they have not been used in any important military capacity in hundreds of years, trebuchets are awesome pieces of engineering that still create excitement in today’s society. Many teachers also use trebuchets to teach the fundamentals of physics to their students, and hobbyists build huge devices to enter in competitions that require the trebuchets to launch a wide variety of objects including pumpkins, pianos, cars, coffins, and even the builders themselves [8]! Trebuchets may be dead on the battlefield, but they are still very much alive in the hearts of students and hobbyists who take joy in discovering the workings of these amazing machines.