Abstract:

In the technological age, most of a person’s daily life can be completed through their device, including dating. Apps such as Tinder, Hinge, and Bumble allow people to connect, but for people of color, especially women, the already difficult dating landscape has acquired a new dimension. The racism, sexism, and overall discrimination they face in regular life has found its way into these apps, illuminating how difficult it can be for women of color to find love. While these apps have created safeguards to protect these groups, it is important to recognize how our social issues can bleed into online interactions and what it says about how our technology must intersect with societal action.

The Modern Dating Landscape

Dating at any age is hard. The idea of opening yourself up to a stranger, hoping that they reciprocate, can be weird and unsettling. It can also become annoying if those interactions happen often, not wanting to experience the mundane questions of “What do you do for work?” or “What are your hobbies?” date after date. It’s hard out here, and with recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, finding a suitable partner has become a frustrating ordeal for some. One group that has it especially hard is women of color.

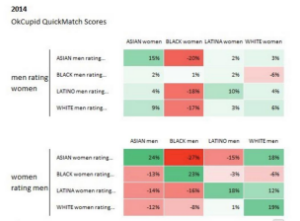

Women’s Health author Tayo Bero identifies that institutionalized racism and white supremacy elevates the position of white women in the dating landscape while demeaning other groups [1]. While her original article was more focused on the experience of Black women’s dating issues, these problems apply to all people of color (POCs) on varying levels. Considering how Black women were consistently rated as less desirable on OkCupid compared to Asian, Latina, and White women, it is important to recognize that blackness or more African features are continuously seen as the most “undesirable.”

Fig 1: Asian and Black men also experienced lower ratings by women compared to White men. [2]

Additionally, according to Bero, colorism and the proximity to whiteness can create additional intra-racial problems for women of color [1]. An important term that adds context to the situation is colorism, which is the “prejudice or discrimination especially within a racial or ethnic group favoring people with lighter skin over those with darker skin” according to Merriam-Webster [3]. Women of color across all racial groups experience this and are told the more “white” your features are, the more attractive you’ll seem. This is why the compliment, “You are pretty for a dark-skinned girl,” can be extremely abrasive. It gives darker-skinned women the impression that they are automatically seen as less because their features are not similar to those of Europeans. It is important to highlight that this happens within a specific cultural group, meaning that women not only have to be judged outside of their race, but they also have to compete on a scale of “whiteness” within their race to be accepted.

A final consequence Bero mentions is that women of color face the possibility of being “exoticized and fetishized” when dating outside of their race [1]. A concern many women of color may have when entering an interracial relationship is how much their partner likes them for their race or culture rather than who they actually are as a person. Common examples of this can be seen in the term “yellow fever” or “jungle fever,” which are the fetishization of Asian women and Black women respectively. But a less discussed form of fetishization can also be someone purposely looking for people who can help them achieve the desired traits in their offspring. It’s one thing to hope that your children have your eyes, but if you want your children to specifically have “light eyes and light hair,” that could be deemed a fetish. These patterns in exoticization and fetishization can lead to uncomfortable situations where the partner treats them more like a

trophy or object to be paraded around, instead of sincerely taking stock of the person and their true relationship to their culture.

These problems are not only seen in heterosexual relationships but also LGBTQ relationships as well, meaning that women of color are constantly finding themselves seen as the less desirable “other.” The modern dating landscape brings about the intersectionality of gender, race and ethnicity, and sexuality in a way that makes many women of color feel isolated to the point where they either settle into a less optimal relationship or completely withdraw from dating.

How Dating Apps Work – For Better or Worse

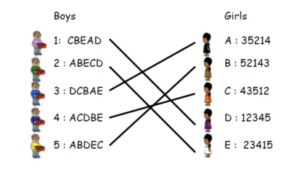

Hinge, one of the more well-known dating apps among the younger demographic, has an interesting algorithm to increase the likelihood of finding matches. They use what is called the Gale-Shapley algorithm, which focuses on finding optimal matches based on how you interact with other users. In the words of Vice, it all comes down to “who you like, who you send comments to, [and] who you are having conversations with.” [4] Using this information, they try to put you into what is called a “stable match.”

Imagine that you are able to rank all of the users currently on Hinge except for yourself, and all of its other users do the same thing. Hinge’s goal with Gale-Shapley is to put you into a pair with someone else where your rankings for each other are as high as possible, meaning that you can’t be placed in a better match. This differs from algorithms seen within other dating applications, such as Tinder. Previously, the app would give users an “Elo score,” where your level of desirability depended on how many people swiped yes on you and who swiped yes (i.e. if hot people liked you, that essentially made you hot stuff too!) [6]. However, it has been

speculated in recent years that Tinder’s algorithm is more closely related to Hinge now, focusing more on matching people by how similar they are and less on how socially desirable they may seem.

Fig 2: An example of how Gale-Shapley works. [5]

Something that makes Hinge particularly intriguing is that within the advanced filters, not only can you set a standard for features including the height and religion of the people who come across your feed, but you can also filter people out by race or ethnicity. While we can say that a racial filter could be useful for POC groups that would like to see other POCs or are more comfortable dating within their race, we must also recognize that people who are racist or xenophobic can use these same features to filter out minorities. It’s difficult to say whether this is a good thing or not because on the one hand, BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and

People of Color) members do not have to suffer harassment from these people but, on the other hand, allowing an “out of sight, out of mind” system doesn’t address the root problems. There are so many negative effects that can stem from the amount of ingrained bias within users’ social views and the algorithms enabling their behavior that we need to hold these apps responsible for educating their users.

It is important to note that sadly, many people may not accept this reform. Part of why these apps succeed and why people continue using them in the first place is that their behaviors are not policed. Therefore, if the previously described methods or the conversations surrounding them become more prevalent on dating apps, people might abandon the app altogether or find less strict dating apps to use. This is why these tactics must be slowly integrated in, focusing first on implementing guidelines that can discourage negative behaviors and then moving on to actually generating conversations surrounding the subject. Like the many other areas of discrimination that minorities and women face today, these attempts will not be completely successful until society changes, but they can help point us in the right direction.

What This Means for Women of Color

Even though women of color do have to face these obstacles when trying to find a partner, it’s imperative that we create spaces that are made for us by us if these applications are not going to take charge. We can always look to our community of fellow WOC to unpack what we’re experiencing because our trials are likely not unique. Having another person who understands exactly what you’re talking about — even without fully having to share what’s going on — can be incredibly freeing and comforting. And this community can come in the form of friends, but it can also be a licensed professional who is also a woman of color. Once you find the right person, their credentials will only enrich the experience because they can offer productive help and work through any of the disappointment, frustration, or even anger that can be found in these situations, because they are tuned in to what you see daily

Additionally, it can also be helpful to look for spaces, online and in-person, that are more in sync with the experiences of people of color. These can include dating apps actually marketed towards minority groups, but this can also be something as simple as attending an art show aiming to uplift BIPOC artists. What experiences like this can show is that there is truly so much beauty within being a person of color. It can be difficult when you’re constantly being compared to the standard when the standard looks nothing like you, but spaces such as these exist to show you that there are people who look like you and are thriving. There is so much life to give and to live within us, and we, as women, are just as deserving of love, and respect, and admiration.

References

- T. Bero, “Dating discrimination against black women isn’t talked about enough,” How Black Women are Navigating Dating Discrimination, 14-Feb-2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.womenshealthmag.com/relationships/a38945511/dating-as-a-black-woman discrimination-racism-colorism/. [Accessed: 03-Apr-2022].

- A. Kleinman, Black people and Asian men have a much harder time dating on Okcupid, 06-Dec-2017. [Online]. Available:

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/okcupid-race_n_5811840. [Accessed: 03-Apr-2022]. 3. “Colorism definition & meaning,” Colorism Definition. [Online]. Available: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/colorism. [Accessed: 03-Apr-2022]. 4. N. Baah, “How does the hinge algorithm work?,” How Does the Hinge Algorithm Work?, 06-Jun-2020. [Online]. Available:

https://www.vice.com/en/article/z3e3bw/how-does-the-hinge-algorithm-work. [Accessed: 03-Apr-2022].

- B. Bravis and B. Rider, “Cleveland State University.” [Online]. Available: https://www.csuohio.edu/sites/default/files/GAGICH%202021.pdf. [Accessed: 03-Apr-2022].

- A. Xiao, “From a swipe to a soulmate – the power of online dating,” USC Viterbi School of Engineering, 21-Oct-2021. [Online]. Available:

https://illumin.usc.edu/from-a-swipe-to-a-soulmate-the-power-of-online-dating/. [Accessed: 03-Apr-2022].

- L. F. Brathwaite, “Why dating apps are racist af — with or without ethnicity filters,” 21-Aug-2020. [Online]. Available:

https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/dating-apps-grindr-ethnicity-filters -1047047/. [Accessed: 03-Apr-2022].