Wine has been enjoyed for over 7,000 years and through the centuries it has been the preferred drink of the Egyptians, Romans and Mesopotamians. It has played a key role in religion and cross-cultural trade, but only in the past 150 years has science and technology become a part of the winemaking process. Louis Pasteur’s discovery of germ theory led to the modern process of winemaking: growing and harvesting, crushing and pressing, fermentation, clarification, and aging and bottling. Winemakers are both engineers and artists, using scientific principles while adding their own unique twist to the process in order to create what they hope will be that perfect bottle of wine.

Introduction

Wine has been the preferred drink of many civilizations through the centuries (Fig. 1). During Roman times it was a symbol of wealth and power, and during the Middle Ages it was the only beverage safe enough to drink. It has been central to widely practiced religions like Christianity and Judaism, it fueled ancient economies, and it spurred cross-cultural interactions and trade. Wine has also been a central element of major civilizations such as the Egyptians, Romans, and Mesopotamians. Although the making of wine in its early stages was far from being an exact science, developments in science and engineering since then have come to play a key role in the way we produce this highly regarded beverage.

Origins

Wine may have been around for much longer than any of us would have guessed — winemaking is now believed to go back as far as 5000 BC, after archaeologists discovered a broken jar with a yellowish residue inside. The jar was excavated from Hajji Firuz Tepe in the northern part of Iran near what is believed to have been a major trade route. It was at that time, during the Neolithic period, that winemaking turned into an intentional human activity as opposed to a natural happenstance [1].

Evolution of Wine Industry

Winemaking, in its simplest form, is an entirely natural process that requires no human intervention. For this reason, no significant changes in viticulture (the study of grapes) or enology (the study of wine and winemaking) occurred until around 1860 AD. The quality of wine in its natural form, however, was generally very poor. Louis Pasteur dramatically changed methods of wine production with his discovery of germs and germ theory in 1861. His contribution illustrated that the problems of the wine industry could be solved by applying the scientific method. He also applied germ theory to fermentation and was able to distinguish differences in various types of yeast. Research in viticulture and enology soon became a worldwide effort and science has since played a crucial role in the production of wine [2].

Overview of the Process

There are five basic steps that go into the production of wine: growing and harvesting, crushing and pressing, fermentation, clarification, and aging and bottling. Although these steps are generally followed, every winemaker has his/her own twist on the process and the number of variations is essentially limitless. In this way, winemakers are both engineers and artists, utilizing science, trial and error, and personal preference to produce a unique bottle of wine.

Growing and Harvesting

Most experts would agree that the grape makes the wine. Grapes (Fig. 2) are the most widely-used fruit in winemaking because their natural sugar and acid content is ideal for the process. Since grapes are the raw material that goes into wine, the composition of a grape “intimately influences the type and quality of wine that can be produced” [1].

Many studies and applications have gone into the growing of grapes to ensure that the best possible wine is produced. These studies have found that grapes are especially responsive to changes in climate; a grape grown in a warm region will be chemically different than the same grape grown in a cool region. This dramatic effect of climate on the quality of grapes has fueled numerous climate-control studies in order to discover which regions are ideal for producing certain types of grapes. For example, a Cabernet Sauvignon grown in Fresno, California, which has a sunny and dry climate, has about 0.65 percent acid; the same grapes grown in Bonny Doon, California, which has more of a Mediterranean climate, have about 1.10 percent acid. Winemakers play the role of chemical engineers as they alter the chemical composition of grapes with climate control in order to produce the best wine possible [3].

Intelligent hybridization of plants has also been researched by scientists and winemakers alike. Hybridization is generally used to protect vineyards from diseases such as phylloxera (root louse), which plagued many European wineries at the beginning of the 20th century. Today, much of the interest in hybrids has been for the development of varieties that are resistant to cryptogamic diseases. The vine itself has also been intensely studied, and hybridization has been used to increase a vine’s productivity and resistance to disease [3].

After the perfect grape has been created and selected, it must be grown in the vineyard (Fig. 3). Once the grape is ripe, the process of harvesting begins. In order to make a good wine, the grapes must be picked at precisely the right time. This is typically done when the grape is ripe, but the harvesting period may vary depending on the particular winemaker’s needs and preferences. The actual harvesting of the grape can either be done by hand or mechanically. Many winemakers then sort the ripe fruit from any bad or rotting ones before the next step, crushing.

Crushing and Pressing

Crushing the grapes was originally performed by men and women stomping in large barrels full of grapes. The resulting mixture of juice, skin, and pulp is called “must.” The process of creating must has since been automated; mechanical crushers now do the work to ensure sanitation. This is also the point in the process that distinguishes a red wine from a white wine. Grape juice is clear, and the pigmentation (or color) of the wine comes primarily from the skin of the grape. Color extraction depends on how long the juice is in contact with the skins. For a white wine, the must is usually pressed right after it is crushed in order to remove the skin and prevent discoloring. Red wines, however, are generally pressed after the fermentation process has begun or is completed in order to create their familiar dark red color [2].

Fermentation

The fermentation process is often considered the magic of winemaking. It is a natural process and human intervention is only necessary to increase clarity and consistency. The key element in the fermentation process is yeast: a microscopic, single-celled fungus. When yeast comes into contact with the grape juice, a chemical reaction converts the sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide:

C6H12O6=>2C2H5OH + 2CO2(1)

Wild yeast is generally present on the grapes, and this allows fermentation to occur naturally; wild yeast, however, is difficult to control and predict. For this reason, many winemakers sterilize the must first before adding their own strain of yeast that they are better able to control. Modern winemakers also add a small amount of sulfur to the must to kill off the wild yeast [2].

Fermentation involves many considerations. For example, temperature plays a very crucial role. If the temperature is too low, the yeast will not consume any sugar but will instead remain dormant in the wine. If the temperature is too high, then the yeast will ferment but simultaneously increase the production of unwanted enzymes and other micro-organisms, which can tarnish the flavor of the wine. The ideal temperature for fermentation is around 72 °F, although this can vary for different types of yeast [2].

There are two stages of fermentation: aerobic (with air) and anaerobic (without air). In the first stage, the mixture is open to the air as the name suggests. During this stage, the yeast rapidly reproduces, and this usually only takes around two to four days. During the second stage, the mixture is sealed off from the air and this is when the majority of the alcohol is produced. Under ideal conditions, the anaerobic fermentation should only take approximately three weeks, but in reality, it may take months. Once the wine has reached its ideal sugar content (for most wines, this is when the sugar is completely gone, but for a sweeter wine there will still be some sugar left), fermentation of the must is stopped by killing or removing the yeast cells. This can be done either by chilling the must or by filtering out the yeast cells [2].

Clarification

Clarification is the next step in the process, and it is used to ensure that the wine is clear and particle-free. This part of the process does not significantly affect the taste of the wine but rather “cleans-up” the appearance of the wine in order to make it look more appealing to the consumer. There are numerous methods for clarifying wine, but the most widely used include racking, cold stabilization, and fining. Racking is the oldest known technique of clarification and relies on the principle that larger particles and impurities will sink to the bottom of the barrel. The clear wine is then siphoned from the top of the container, leaving the larger particles at the bottom. Another process is cold stabilization, which is used to remove the tartaric acid that may later crystallize in the bottle. The wine is warmed to room temperature and then chilled to 40 °F, which crystallizes tartaric acid. The wine is then racked and the tartaric acid remains behind. Fining is yet another process for clarifying or stabilizing the wine. The winemaker adds a fining agent to the wine that is heavier than both water and alcohol and does not mix with either. The agent traps small particles in the wine and then sinks to the bottom. During the siphoning process, the particles and the fining agent are left at the bottom [2].

Aging and Bottling

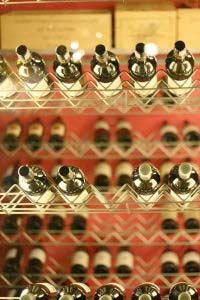

The final step in the winemaking process is the aging and bottling of the wine. Some wines are bottled immediately after the clarification process but most are left to age. Wine can be aged in barrels of oak or other woods and these wooden barrels impart flavor and aroma to the wine (Fig. 4). Different types of wood can affect the types of flavors as can the age of the barrel itself. Bulk aging, when large quantities of wine are aged together, is generally considered better because bulk amounts are less affected by changes in temperature. The quality of wine can be ruined by both heat and sunlight, and it is therefore best to age wine around 50-60 °F and in dark places. Different types of wine also require different amounts of aging. For example, a full-bodied red wine needs to age for at least one to two years while a fruity white wine only needs to age for around three months [2].

After the wine has properly aged, it needs to be bottled. There are now advanced devices for bottling that automate the entire process. Machines sterilize the bottles, standardize the fill line, insert corks, cover them with caps or foil, attach a label, and box them for storage. Some wines are left in refrigerated tanks to ensure their freshness and are then bottled periodically throughout the year to restock.

Conclusion

The process of winemaking has existed for around 7,000 years, but only in the last 150 years has the science behind it been understood. Engineers and scientists have since improved the process by making it more consistent and efficient, but there is still much about wine making that remains elusive. Taste is very subjective, making it nearly impossible to predict exactly how a consumer will react to a certain bottle of wine. There is no doubt that winemakers and scientists have greatly contributed their expertise to the process, but there is still more to be discovered about the art and science of winemaking.