Do androids dream of electric sheep? The answer lies within Google’s new image recognition algorithm, DeepDream. While the algorithm is more generally used to identify objects in images, it can also be used to give images a “dreamy” makeover. To fully understand what DeepDream is, and how it gives images these bizarre makeovers, we must dive into the world of “neural network” computer systems that attempt to mimic the problem-solving ability of the human brain. To increase their intuitive ability, neural networks can be trained with study guides and evaluated by tests– not much different from the way that students learn. Overcoming one of the great challenges of computer science, DeepDream utilizes complex structures to achieve object recognition within provided images.

Introduction

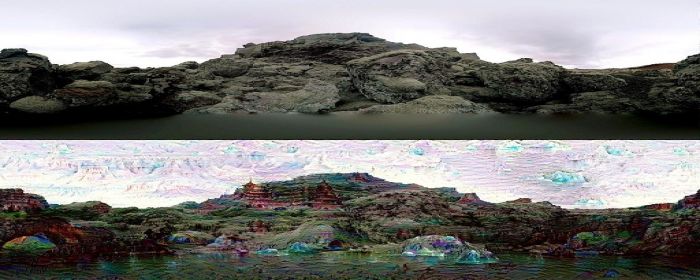

Google recently released DeepDream, an image classification program. Simply put, image classification is the process of analyzing an image and determining what exactly is in it- be it a dog, tree, or balloon. Object recognition is considered to be one of the most difficult challenges facing modern computer scientists. Progress in image classification relies on our ability to truly understand and electronically replicate human sight. DeepDream makes significant strides in improving image classification because of its advanced internal structure that mimics the human brain. One of the more interesting outcomes of DeepDream is an overlay of trippy and bizarre visuals, comparable to drug-induced hallucinations, as it attempts to “see objects”, as seen in Fig. 1. But how does image classification lead to these outlandish images? To understand these bizarre image overlays, we must first understand the neural network that constitutes DeepDream’s internal structure.

A. Mordvintsev/Research Blog

Figure 1: Places In Rocks: The above image is produced by a variation of the DeepDream algorithm trained to recognize “places” [1].

Artificial Neural Networks

A neural network is essentially computer science’s take on the brain. To understand the motivation behind neural networks, we must first think about how computers solve problems. It’s surprisingly difficult to describe what a computer can actually do. Computers are incredibly good at some things – like telling you the millionth digit of pi in a few milliseconds – but incredibly bad at others – like figuring out whether or not a photograph contains a bird. While this distinction may seem arbitrary, the ability of computers to perform certain tasks depends completely on its internal algorithms. Algorithms, collectively, create the brain of a computer. They serve as intricate instruction manuals to solve specific problems. They work reasonably well for problems we know how to solve, like algebra, for it is easy enough to explain the steps of equation simplification. But how would you describe the process of determining whether or not a photo has a tree in it? Although trees come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and colors, they share certain common features– roots and branches, for example. While it might work to simply establish the presence of these common features in an image, it would be a lot of work to compile and recognize the variety of features that trees exhibit. Our brains, in comparison to algorithms, are much more capable of solving these types of problems. There is simply no general method to recognize a tree that is as straightforward as simplifying a math equation.

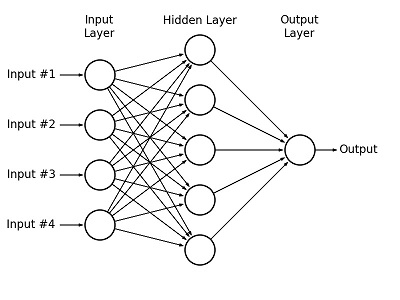

To answer this challenge, computer scientists have developed computer system neural networks to mimic the problem-solving capacity of the human brain. Similar to how neurons are the building blocks of the brain, perceptrons (basic components which outputs either a 1 or a 0 depending on its inputs) are the building blocks of neural networks. Fig. 2 diagrams the basic structure of a neural network. Perceptrons, here represented as circles, are placed in multiple layers. The problem is fed to perceptrons as encoded inputs in the input layer. The perceptron output from the input layer is then passed on to a number of “hidden layers.” Finally, the processes inputs are passed through the output layer and a cohesive solution is presented in response to the original problem.

AstroML/AstroML

Figure 2: Neural Network Structure. Source: AstroML.

Each input for a perceptron has a weight associated with it. The input is multiplied by its weight, resulting in the weighted input [2]. The weighted inputs are then summed, and this value determines the output of the perceptron [2]. The weight on each input is the source of a neural network’s versatility. By tweaking the weights just right, a neural network can approximate any given function [3]. Then, the issue becomes picking the right weights. Considering how difficult it is to not only pick the right weight, but also to know whether or not it is the right weight this isn’t the most feasible solution. If only there were a way for a neural network to learn what the weights should be.

Neural Network Learning

Neural network learning is simple- in theory. We feed the network an input, and tell it what the expected output should be. With a complex calculus method called “gradient descent,” the network can figure out how to adjust its weights by an infinitesimal value to minimize error [2]. For every input, the neural network compares its output with the expected output. The neural network then uses gradient descent to fine tune and shift the weights to minimize error. Once the network receives the correct output, the weights remain unchanged. When training a neural network, scientists typically use two-thirds of the inputs as a “training set.” The remaining third of the inputs is the “test set,” which essentially tests the neural network by providing it with an incorrect answer. To review, the training set is the network’s study guide, which is used to prepare for the final exam: the test set. These two sets are separated to prevent the network from “cheating,” similar to the way a professor will not provide students with answers to an exam before it is administered. Consequently, the neural network learns how to solve complex problems and can adapt to work with unknown inputs.

This algorithmic approach to learning leads to a troubling conclusion: the precise methods that allow these networks to function remains unclear. While we know how to create them, the internal mechanisms are virtually impossible to understand. For example, in the 1980s, the Pentagon attempted to build a neural network that would determine whether or not a photograph contained a tank [4]. After the neural network was trained with 200 example photographs, it reached perfect accuracy [4]. However, when given new inputs outside of the example set, the outputs were completely random [4]. Despite the fact that it learned from such a large training set, on its own the neural network was no better than flipping a coin. It was only after many years that someone realized the problem: all of the example photos with tanks were taken on cloudy days, and all the photos without were taken on sunny days [4]. With some of the brightest minds in computer science, the Pentagon had created “a multi-million dollar mainframe computer that could tell you whether [a photo] was sunny or not” [4].

In addition to the neural network error caused by unforeseen similarities in training sets, other errors can be caused by overfitting [2]. If a network has too many perceptrons, it could simply memorize all the examples, avoiding learning altogether. Luckily, networks can be retrained with different sets, only saving the results if it increases performance – much like when you save your progress in a videogame and reload every time you fail until you finally beat the level. Making sure a neural network not only learns, but also learns the right thing, is incredibly difficult. Luckily, computer scientists have been working since the 1940s to optimize these complex structures. All this work has come to fruition in today’s age, when computers are finally able to recognize images – which brings us back to DeepDream.

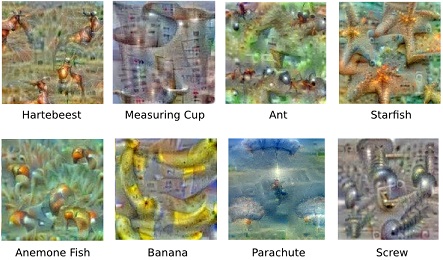

Google’s DeepDream

DeepDream is Google’s codename for their neural network trained to recognize specific types of images – think of an improved and functioning version of the Pentagon’s fancy neural network. The neural network is trained to recognize a specific type of image – whether it’s as general as “places,” or as specific as “tanks” [1]. So, these neural networks are trained to “see” (as best as a computer can) a specific class. Fig. 3 gives different examples of what DeepDream exactly sees. It’s not exactly what we, as humans, see, but the resemblance is evident.

A. Mordvintsev/Research Blog

Figure 3: Different Image Classes [1].

While Fig. 3 may seem strange, it doesn’t compare to Fig. 1. In Fig. 1, DeepDream produces an image, and then that same image is fed back into DeepDream. This continuous, “Inception”-like looping is what causes the drastic differences between the input and final output [5]. A closer look at Fig. 1 shows the neural network looking for what it’s trained to see. After many iterations, the rocks slowly transform into buildings and pagodas. Each iteration of DeepDream morphs the image slightly, as it attempts to “see” the objects it’s trained to see. Even if these objects aren’t present, as is the case with Fig. 1, the network tries to perceive them from something that looks similar [5]. This feedback loop eventually creates pronounced images which weren’t even in the original image. DeepDream and, by extension neural networks, are incredibly powerful. While they have been under active research for over 70 years, they are still in their infancy.

Neural Networks in the Future

While computers routinely fail in some complex areas, it’s clear that neural networks show promise in these problem spaces. Consider the pure computing power of computers combined with the plasticity and versatility of the human brain. The possibilities are endless. DeepDream has already shown potential in the field of image recognition and processing. Future advancements could do more than create trippy images – it could lead to robots with human-like vision with artificial eyes [6]. For the more financially inclined, a properly trained neural network could analyze the stock market and predict future trends [6]. In the field of thermodynamics, neural networks could learn to predict vapor-liquid equilibrium data for various substances [7].

The list of potential applications is endless. However, the loftiest goal with neural networks is to advance artificial intelligence [2]. Russell and Norvig believe that neural networks are essential to properly simulating intelligence, a theory which sounds incredibly logical. It intuitively makes sense that the best application of an electronic structure that mimics the brain is to recreate human thought processing. A fully capable artificial brain could introduce a new trend of neural network enhanced androids and ultimately revolutionize the concept of humanity. And who knows- maybe these androids will dream of electric sheep after all! We may be light years away from this concept, but DeepDream is the first step toward understanding the vast capabilities of the neural network.

References

-

- [1] A. Mordvintsev, “DeepDream – a code example for visualizing Neural Networks”, Research Blog, 2016. [Online]. Available: http://googleresearch.blogspot.com/2015/07/deepdream-code-example-for-visualizing.html. [Accessed: 09- Feb- 2016].

- [2] S. Russell, P. Norvig and E. Davis, Artificial intelligence. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2010.

- [3] M. Nielsen, “Neural Networks and Deep Learning”, Determination Press, 2015.

- [4] N. Fraser, “Neural Network Follies”, Neil.fraser.name, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://neil.fraser.name/writing/tank/. [Accessed: 08- Feb- 2016].

- [5] A. Mordvintsev, “Inceptionism: Going Deeper into Neural Networks”, Research Blog, 2016. [Online]. Available: http://googleresearch.blogspot.com/2015/06/inceptionism-going-deeper-into-neural.html. [Accessed: 08- Feb- 2016].

- [6] Cs.stanford.edu, “Neural Networks – Future”, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://cs.stanford.edu/people/eroberts/courses/soco/projects/neural-networks/Future/index.html. [Accessed: 09- Feb- 2016].

- [7] R. Sharma, “Potential applications of artificial neural networks to thermodynamics: vapor–liquid equilibrium predictions”, Sciencedirect.com, 2016. [Online]. Available: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0098135498002816. [Accessed: 09- Feb- 2016].