With Americans working longer hours, there is less time to create a meal from scratch. The invention of frozen food has allowed us to simply microwave a meal in a few minutes, providing us with more time to spend on our hobbies and with our loved ones. Although some people tend to stay away from frozen food due to their perceived low nutritional value, frozen vegetables and fruits are actually more nutritious than their fresh counterparts. The flash-freezing technology is responsible for trapping the vitamins immediately after the produce has ripened, which helps maintain the flavor and tenderness. The frozen food industry continues to grow and expand as more people realize its nutritious qualities and want to spend less time preparing meals.

Introduction

Arriving home famished after a hectic work day of meetings, clients and hundreds of emails, you reach inside your freezer for some quick nourishment. Frozen dinners, pizza, and vegetables rest scattered inside the cold compartment. You pick the frozen peas and lemon-herb chicken from a pile and heat it in the microwave. Ten minutes pass and ding! Dinner is served. The piping-hot chicken, surrounded by its clear juices, appears plump and succulent. The round and vibrant green peas burst with tenderness in every bite. The meal tastes and looks like you slaved many hours in the kitchen. However, it only took you a few minutes.

The time consumption and complexity of preparing meals have been eliminated since the invention of frozen food. You no longer need to spend hours to purchase ingredients, prepare the items and cook for a meal that takes few minutes to consume. All the work has been done for you by the time the food is purchased. This convenience is becoming very important with more people working longer hours at the office and wanting to spend more time with love ones outside the kitchen. The American frozen food industry has steadily increased each year and by 2006 reached $28.1 billion, a 1.8% increase from the previous year [1]. With such a revolutionary and popular product, it is important to understand the history, process, nutritional value, impact and future of frozen foods.

The Beginning of Flash Freezing

Since the process of cooking frozen food on the consumer side is simple, the complexity of creating the frozen food you buy in supermarkets is often overlooked. This process has been delicately engineered over the past decades to ensure that your meal comes out with the same nutritional qualities, flavor, and texture as if you cooked it yourself. American biologist Clarence Birdseye discovered the modern-day process of freezing food using the flash-freezing technology. While on an expedition in the Arctic, he witnessed Eskimos catching fish. These fish froze instantly in the glacier air and yet retained their full qualities of freshness upon thawing. Freezing prevented the fish from spoilage by slowing the active enzymes that would otherwise break down the flesh and produce ammonia [2]. However, this freezing process needs to be completed quickly, before the enzymes can spread all over the fish.

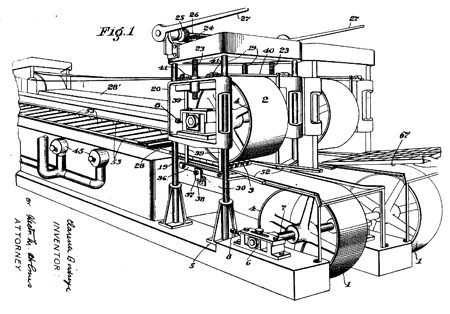

Using this principle of frozen fish as a basis, Birdseye realized that slowly freezing foods caused the formation of large crystals and micro-organisms, which would damage the cellular structure of the food and render it inedible. But if the food was frozen quickly, then the original cellular configuration could be preserved to lock in freshness and good taste. To accomplish this, Birdseye invented the Multiplate Quick Freeze Machine, a “double plate” freezer in the 1920s, which is shown as Fig. 1.

This machine used actual new garbage cans with layers of steel plates. The food was placed in between the plates and passed through a freezing tunnel of coils carrying calcium chloride brine (salty liquid) chilled to 40°F. This system managed to cut freezing time from 18 hours to only 90 minutes, which greatly improved the quality of the frozen foods [3].

Today’s process of quick freezing still stems from the principles Birdseye discovered. Food needs to be frozen quickly to prevent the cellular structures from deteriorating and changing the taste and texture of the food. However, given the advancement in freezing technology, Birdseye’s garbage-can-and-steel-plates freezing mechanism is no longer used to freeze your dinner. Depending on the food type, there are different systems available that utilize quick freezing technology.

The oldest and most common freezing apparatus used today is the air-blaster freezer. Its constant temperature and versatility with differently shaped products make this freezing mechanism the most popular choice. The temperature is kept constant by shooting cold air into the freezing room, allowing the uniform freezing of unprocessed products like meats, which would otherwise freeze unevenly, causing spoilage. Inside the freezing room, there is normally one fan and one cooler. The fan is positioned on the left side of the cooler so the cool air can circulate in a clockwise direction. When the product arrives at the freezing site, it moves in the direction of the arrow so the coldest air is encountered at the end. Once the product reaches the most frozen air, a final icy preservation layer seals over the entire item and the freezing process is complete [4].

Focusing in: Fresh to Frozen Peas

The process of frozen foods neither starts nor ends with the use of quick-freezing technology in air-blaster freezers. All vegetables, fruits, and meats must be properly prepared before entering the freezer, and the frozen product is carefully analyzed by quality control workers afterwards. For example, frozen peas (Fig. 2) have a multi-step process that only lasts a few hours, but which transforms the freshly picked peas into the variety you buy in your grocery store’s freezer. This process begins at the farmland. Fresh peas that are frozen are actually cultivated for that specific purpose. Producers require the farmed peas to have sturdy shells and a hard interior to minimize the damage done by freezing. When these special varieties have ripened, they are picked by hand or automatically by a machine. Then a specialized machine sorts through the peas and removes them from their shells. The peas are cooled with ice water and then packed in ice, ready to be transported to the freezing plant.

Once the chilled peas reach the plant, they are sprayed down with water to remove the dust and dirt. Then they pass through a vat of boiling water where they are blanched for a couple of minutes. Through blanching, the enzymes, like those in the fish, are killed to prevent further spoilage while retaining taste. Afterwards the peas are cooled down from the boiling water and transferred to a gravity sorter, where they are immersed in brine to be separated by texture. The tender peas float to the top while the starchy ones sink to the bottom.

When the tender peas have been picked out, they are rinsed again to remove the salt remnants. Once clean, they are sorted again by human workers, who inspect the peas as they pass through on belts and pick out the discolored or irregularly shaped peas, rocks, and debris from the pile. At the very end of this process, only the top quality peas remain, ready to be frozen.

Peas are frozen using the same quick-freezing process found in the air-blaster freezers. The clean peas are placed in the freezers and are moved through the room so that in just 15 minutes, the peas are frozen and ready to be packaged. The packaging stage has now become fully automated. The frozen peas travel on a belt where mechanical equipment packages them and then stacks them in a case. The cases are arranged in pallets to be stored in a warehouse cooled between 0 to -20° F. Finally, when the peas are ready to be distributed to grocery stores, they are carried in trucks or rail cars cooled to 0° F or below [4].

Quality Assurance

Throughout this process of preparation, freezing and packaging, frozen food is inspected to ensure quality is maintained. Laboratory workers pull random samples from different stages of the process to test for bacteria and foreign matter. At the end of the process the workers also cook and taste them to verify that the freezing process hasn’t compromised the taste and texture of the product. The machinery used for the creation of frozen foods is also quality-controlled. Over the years, the equipment has been developed so it is easy to sterilize and clean between processing of different food types. Laboratory workers also test and clean the machines at specified intervals so that they are completely sterile. Given all these regulatory measures, the safety of consuming frozen food is no different than that of the fresh produce [5].

Fresher Than “Fresh”

For most people, frozen food reflects a lifestyle of convenience, not of nutrients, taste and flavor. So when deciding whether to go down the fresh produce or freezer aisle in the grocery store for a healthy dinner, you will most likely find yourself picking out the fruit and vegetables from the stands and not from a freezer. Fresh produce must be better since it was handpicked by the farmers, right? No!

The fresh fruit and vegetables you find in the market are often picked during an immature state and allowed to ripen “off the vine” during the transportation and storage stages. Therefore by the time they actually appear in the produce stands, the vegetables have already lost some of their vitamins. Then when you take the produce home, they continue to lose nutrients while being stored in the refrigerator. Air exposure becomes much more destructive to volatile nutrients like vitamin C. Peas lose about 40% of their vitamin C just three days after they are picked [7].

However, since frozen vegetables and fruits are packed immediately after harvesting, they still maintain most of their nutrients. In fact, by consuming a four ounce serving of frozen orange juice, you will have nearly satisfied the recommended daily amount of vitamin C, folic acid, and potassium. The same amount of fresh orange juice, however, will give you about a third less of the same vitamins [6]. Contrary to what most Americans might envision frozen food to be – high-fat, high-sodium TV dinner – the right type of frozen products can actually be better for you.

Global Impact and the Future of the Industry

The frozen food industry has changed the dining experience for consumers worldwide. Even in Europe, the land of food connoisseurs, the demand for frozen food has actually increased. The Western European frozen food market was worth 65.7 billion euros in 2005 and is forecasted to grow annually at 1.71% between 2005 and 2010 [8].

Specifically, the French spent 5.4 billion euros on frozen food and 1 billion euros on ice cream during that year [5]. And unlike the United States, which sells frozen food only in grocery stores, France has also developed specialized frozen food stores to accompany the French boulangeries and produce stands. These stores sell only frozen products, and some companies like Picard even provide unique catalogue-ordering services and home deliveries to appeal to a wider audience.

With the industry growing domestically and internationally, the future of frozen food does not seem to be cooling down anytime soon. The expanding market brings about more competition between existing companies, and new technologies are emerging to create the best-tasting frozen food possible. Food scientists are finding new ways to create even smaller ice crystals to eliminate all freezing damage. Manufacturers are improving their frozen food supply chain to cut down the time between the produce being picked and its arrival at the grocery stores. Given all these advancements, the quality in taste and nutrients of frozen food will only keep increasing until what you consume resembles its “fresh from the garden” counterparts.