Abstract

As an integrated civilization, we have long sought a cashless society in which sophisticated technological advancements help prevent financial fraud. While the conservative banking industry constantly weighed the cost of production and maintenance against consumers’ unceasing demand for more expediency and security, payment cards evolved from stripes to chips and eventually into contactless cards, just in time to save the economy from the COVID-19 pandemic. Contactless technology has forever changed our perception of how money can be transferred and has further inspired applications in digitizing more sensitive personal information in the near future.

A Cashless Society

Do you find it harder and harder to accumulate fortune in your piggy bank now, just because you don’t have loose change as often ? But doesn’t it also feel easier to send your friends the exact amount of money for movie tickets instead of tracking how much one owes another down to the last cent? As the digitalization wave sweeps across all aspects of the world’s daily operations, each business sector has to find its way of adapting to the era of big data. As an age-old industry, banking is finally taking a step forward but rather reluctantly and with extreme caution.

Cashlessness is not a new twenty-first century dream. Bartering and other forms of exchange also transcend the standardized paper and coin currency and have been practiced since the beginning of human civilization. In the context of massive information influx, however, today’s economists define the real cashless society as one where all monetary activities are created, documented, and circulated in digital form [1]. The idea of a cashless society being so rebellious to societal tradition attracted not only business innovators but literary thinkers as well, such as Thomas More, Robert Owen, and William Morris. In their pre-1900 Utopian fictions, they each envision a world that escapes the materialistic value of the note-and-coin system in pursuit of a simpler carriage of peace and happiness [2].

Existing problems with the use of conventional payment methods fuel the thirst of a safer and cleaner alternative. Financial theorist Nikola Fabris argues that, for starters, the elimination of cash would bring down criminal activities, particularly those connected with drugs and money laundering[1]. Untraceable cash imposes serious safety concerns for individuals as well. As valuable and impersonal as it is, large amounts of cash renders people and places vulnerable to robbery and other related violence [1]. Thus, both personal inconvenience and national insecurity call for a fundamental change in how we pay and what we pay with.

From Magnetic Stripe to Chip-And-PIN

Society achieved its first practical breakthrough towards cashlessness in the 1970s. Like many other great technological advances in history, the benefits of credit cards we enjoy today is a result of a marriage between smart business and innovative engineering. The transition from cash to payment cards is a huge jump toward a traceable and more convenient style of transaction. Although almost every bank today issues credit and debit cards, this form of payment took more than 20 years after its launch to be accepted and standardized across all banks [2]. Since then, electronic payment systems have undergone three major transformations, each propelled by a safer technology.

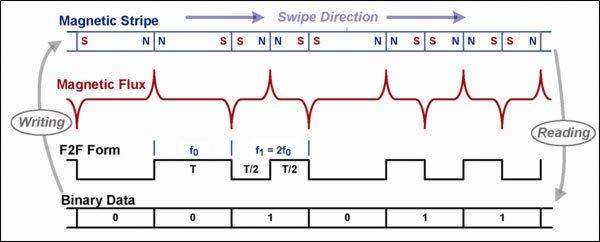

The first stage of digitizing payment information was brought into existence through magnetic stripes on the back of plastic cards. Pioneered by the now multinational technology corporation IBM, magnetic stripes remain the most prevalent way of materializing information onto portable devices. Inspired by the process of ironing clothes, this technology melts a strip of magnetized tape onto a piece of pocket-sized plastic [3]. Figure 1 depicts a technique called two-frequency coherent phase (F2F) that is used when translating between binary data and the magnetic stripe. Each two-unit bar magnet codes a binary 0, whereas a pair of one-unit bars is a binary 1 [4]. Aiming for a worldwide adaptation of this technology, IBM also decided to relinquish the patent to its innovation [3]. Therefore, combined with the extremely low cost of production, magnetic stripes became the go-to option for producing IDs, driver licenses, and passports. According to IBM, stripe cards for all purposes are being swiped through “mag stripe” readers more than 50 billion times a year, changing people’s daily lives from retail to transportation [3].

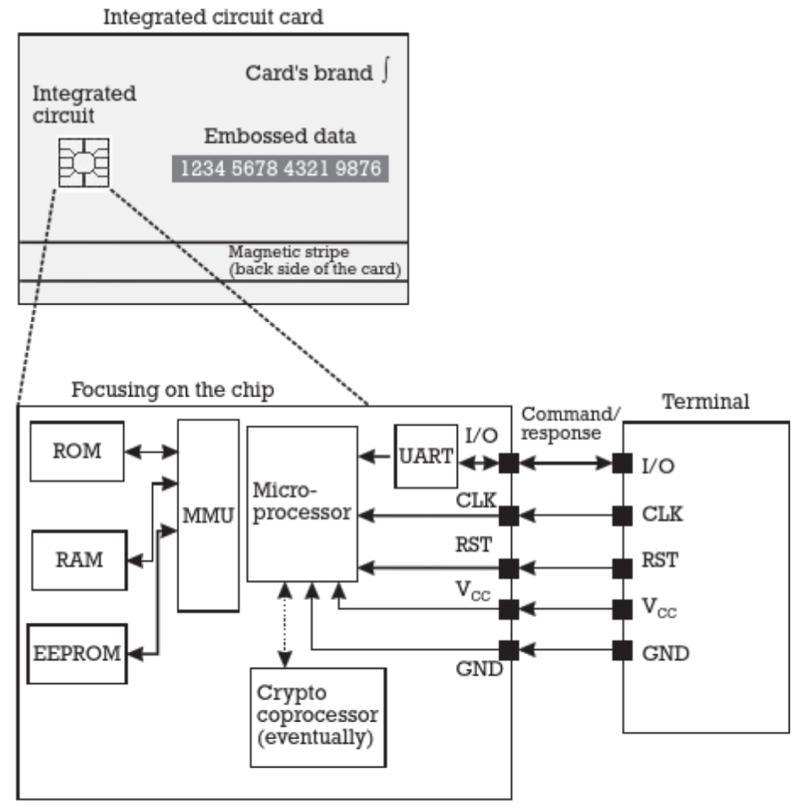

Figure 2 lays out different parts of the microchip and how it connects to an electronic chip-reader. When inserted into a chip reader, data ports on the left end of the chip will complete circuits with each of their corresponding terminal ports on the right, enabling an exchange of commands and responses, usually in the form of accessing and manipulating memories. Therefore, unlike magnetic stripes, which can only present coded information for the receiving terminal to read in, chip cards are equipped with memory storage and processing capabilities to carry out much more complicated tasks. These include encrypting transaction information and prompting the user to manually enter their Personal Identification Number (PIN). On the other hand, chip-readers also require a more sophisticated design and hardware investment such that it connects to an online information reservoir and can instantly authenticate user identity to verify a transaction [5].

The mightiness of such computing machines has come to define the twenty-first century experience. Especially with large transactions, bankers can finally stop drawing their counterfeit pen on every Benjamin Franklin face and start trusting the highly intelligent cryptography algorithm to get the work done. In fact, Visa, the telephone operator between customers and the banking industry, issued its newest statistics claiming that an astonishing 509 million Visa chip cards are now being used nationwide, successfully reducing counterfeit fraud by 76% [6]. That is more than 1.5 Visa chip cards per American hand!

However, apart from the higher cost of production compared to that for stripe cards, chip cards’ sophisticated security feature costs users something arguably more valuable than money––time. Inserting a chip card into its compatible reader, or Point of Sale (POS) terminal, can be challenging for some cardholders. In particular, the less than 0.1-inch opening for the insertion makes payment difficult for elders with poor vision and motility, not to mention the authentication prompt which will appear after the POS terminal reads the chip. Researchers from University of Massachusetts found chip technology to be a double-edged sword; though chips can encrypt the data they send, such an encryption process slows down transactions and elevates the cost to build and maintain the payment networks [7]. With such technological delay on top of the objective existence of cardholders who often forget their 6-digit PIN, checkout lines can get longer than when cashiers used to punch numbers into a calculator, do mental math to figure out how many of which kind of bills to give out, and double count the loose change before handing it back to customer.

Contactless Payment: Benefits and Security Dilemma

As consumers demand more expediency, a new way to “insert” payment cards debuts. By its self-explanatory name, contactless payment refers to a new form of paying where a tap or a wave of cards replaces previous swiping or inserting. The fundamental method of encoding card information and transferring it onto a piece of plastic remains unchanged to a traditional chip card––with an integrated circuit chip. Therefore, contactless payment inherits the same level of security by encrypting data through minicomputers. But instead of inserting the chip into a reader, contactless payment utilizes radio-frequency identification (RFID) to bridge the gap between cards and POS terminals. This technology enables devices in close proximity to “talk” to one another and is widely used to perform other daily tasks, such as package tracking and toll collection [8]. But how do they make sure you don’t walk into a grocery store and pay for everybody’s groceries just because you are carrying a contactless credit card? An improved RFID technology called near field communication (NFC) restricts the distance to a much smaller scale for the transaction communication to be established [8]. As a result, touchless payment shortens each transaction by a few seconds, but it amounts to a huge difference in fields such as public transit and quick serve restaurants [9].

While many consumers typically tend to avoid being the guinea pigs of new technology, especially in high-stake fields such as banking, contactless payment debuted in an extremely favorable market climate: the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus’s alarming contagiousness promotes a cashless society like never before. The US Chamber of Commerce recently warned the public that infectious bacteria and viruses can survive on bank notes and coins. Payment cards can be risky as well if cards are exchanged interpersonally for processing or consumers use touchpads to enter a password or add a gratuity [9]. There the dilemma emerges: contactless payment uses the same chip encryption for security in transactions, but if touchpads are off limits, how should customers enter their PIN to verify their identity?

Collaboration with Smartphone Companies

Prior to contactless payment becoming more prevalent during the pandemic, no-swipe cards and mobile banking each experienced limited acceptance from consumers. After years of PIN usage, many cardholders are hesitant to switch over to the contactless cards which require no passwords, despite banks’ repeated promises of security measures. The reason is simple: on-the-spot authentication, be it PIN or hand signature, feels more tangible and reassuring. On the other hand, mobile financing launches primarily in two forms: banks’ mobile apps, which perform the same tasks as a banker only to save you a trip to the office, or inter-account money transfer services, such as Venmo.

The cultural phenomenon where instead of writing checks for other people, we “Venmo” them the exact amount is a testimony to the ultimate convenience mobile phones can provide. Venmo’s story started out with one of its founders’ clumsiness. He forgot his wallet while going out with friends and couldn’t find his checkbook [10]. Given the boundless capabilities of smartphones today, consumers have become inseparable from them, making these mobile devices an ideal candidate for guaranteed convenience. Inspired by such observation, Venmo now provides the simplest solution (yet) for individuals to transfer small amounts of money straight to another individual account holder. But this kind of mobile money transfer service faces a limitation as well: retailers aren’t individuals who just want to “Venmo” their friends money for pizza. They still rely on banks for their mature safety protocols when managing large or international transactions and their ability to produce documents for taxing purposes. This left banks thinking: Can we synthesize these two promising inventions?

The answer lies in the mobile wallet. Smartphone companies such as Samsung, Apple, and Google all came up with their own virtual wallet apps which allow consumers to load their card and bank account information into their phones and directly pay from there. The mobile wallet employs NFC technology so no physical contact between the mobile devices and POS terminals is needed to complete transactions. At the same time, smartphones’ state-of-the-art encryption technology secures payments and shields user information from merchants with a device-specific number and unique transaction code [11]. To replace PIN authentication, built-in fingerprints or facial recognition softwares are invoked to authorize transactions at the time of sale, which not only prevents identity theft but achieves complete contactless-ness between the buyers and sellers. You can now enjoy the benefits of contactless payment anywhere with a Wifi-symbol turned sideways, and potentially with various portable devices, as illustrated in Figure 3. According to CNBC’s data collection, more than half (51%) of Americans are adapting to different forms of contactless payment, which is a spike from the 3% in 2018, claimed by a global management consulting firm [12], [8]. Knowing changes are hard to implement and consumers lack the desire to convert, it only took a worldwide pandemic to make the age-old banking industry conform.

What’s Next?

While we are optimistic that contactless payment will continue to be the dominant form of payment in post-COVID society, payment technology is still evolving to satisfy every last request from consumers. For example, mobile wallet users inevitably encounter the problem of running out of phone battery. This issue motivates the newest invention of a contactless biometric payment card, which incorporates a fingerprint sensor directly onto the card itself and updates the embedded chip’s algorithms and processing power to accomplish on-card authentication [13]. If such technology is perfected and accepted by the masses, the banking industry might regain its autonomy from the smartphone industry. However, to reemphasize, consumers have a long history of being reluctant to adapt to new forms of technology. Truth be told, the old-fashioned magnetic stripes are still very much present on every single payment card issued in America––chip cards and contactless cards alike––in order to guarantee all cards can be compatible with even the oldest POS terminals. In this sense, we’ve never abandoned our origin.

However, the reverse can also be true. After the digitalization of credit/debit cards, contactless technology has also been virtualizing other cards as well; New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA)’s OMNY tap-and-go transit-fare payment card is one example [8]. This leads to an expectation of a broader application of the technology.What if we can add driver licenses and passports to mobile wallets since they use the same magnetic stripe technology to store information. When monetary transfer is made as easy as texting, we give more power to our smartphones, from navigation to payment, and potentially identity validation. If the risk of losing a phone, or simply running out of battery is so high as to handicap a person’s daily operation, we as a society may have to rethink our dependence on communication technology. Because information theft only gets smarter with time, a hand-sized device that holds all valuable information of a human being can potentially mean that cloning a person may no longer be fictional, at least on a virtual level.

References

[1] N. Fabris, “Cashless Society – The Future of Money or a Utopia?,” Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice (Podgorica), vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 53–66, 2019, doi: 10.2478/jcbtp-2019-0003.

[2] B. Batiz-Lazo and L. Efthymiou, The Book of Payments: Historical and Contemporary Views on the Cashless Society. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016, doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-60231-2_2

[3] “Magnetic Stripe Technology,” IBM. [Online]. Available: https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/ibm100/us/en/icons/magnetic/ [Accessed Feb. 17, 2021].

[4] “IMPROVE MAGNETIC CARD READING IN THE PRESENCE OF NOISE,” Maxim Integrated, July 24, 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.maximintegrated.com/en/design/technical-documents/app-notes/5/5094.html [Accessed Apr. 29, 2021]

[5] C. Radu, “Chip Migration,” Implementing electronic card payment systems. Boston: Artech House, 2003, pp 53-69.

[6] “Chip technology helps reduce counterfeit fraud by 76 percent,” Visa, May 28, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://usa.visa.com/visa-everywhere/blog/bdp/2019/05/28/chip-technology-helps-1559068467332.html [Accessed Feb. 17, 2021].

[7] J. Schwartz, “Researchers See Privacy Pitfalls in No-Swipe Credit Cards,” The New York Times, Oct. 23, 2006. [Online]. Available:

https://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/23/business/23card.html [Accessed Feb. 17, 2021].

[8] S. Walden, “Banking After Covid-19: The Rise of Contactless Payments in the U.S.,” Forbes, Jun 12, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/banking/banking-after-covid-19-the-rise-of-contactless-payments-in-the-u-s/#:~:text=How%20Contactless%20Payments%20Work,readers%20that%20decode%20the%20message [Accessed Feb. 17, 2021].

[9] I. Polyak, “The Coronavirus Is Pushing Wider Acceptance of Contactless Payments,” CO— by U.S. Chamber of Commerce, June 22, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.uschamber.com/co/good-company/launch-pad/contactless-payment-methods-coronavirus [Accessed Feb. 17, 2021].

[10] D. P. Simon, “The Money Hackers: How Venmo Became a Verb,” Financial history, no. 135, pp. 12–17, 2020.

[11] “Cashless made effortless,” Apple. [Online]. Available: https://www.apple.com/apple-pay/ [Accessed Feb. 17, 2021].

[12] A. White, “More than half of Americans now use contactless payments, according to Mastercard poll,” CNBC, Nov. 18, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.cnbc.com/select/mastercard-survey-contactless-payments/ [Accessed Feb. 17, 2021].

[13] H. Nilsson, “Trust issues? The need to secure contactless biometric payment cards,” Biometric technology today, vol. 2021, no. 1, pp. 5–8, 2021, doi: 10.1016/S0969-4765(21)00009-6.

[14] “Contactless Payment is Available on Metrobus and Metrorail,” Miami-Dade County, May 27, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.miamidade.gov/global/news-item.page?Mduid_news=news1563223075280894