Abstract

Skipping a rock across a lake is not as simple as a casual observer might believe. The rock’s dancing motion results from complex dynamics that scientists are still struggling to understand. Empirical modeling published in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics suggests that to maximize the number of skips, a rock should be thrown at approximately a 20-degree attack angle. However, the world record holder for rock skipping, Kurt Steiner, does not use this approach; his throw of 88 skips was achieved with a 30-degree attack angle. This article explores why physicists might want to incorporate human factors, like Steiner’s awareness of nature and its properties, when trying to explain how the universe works.

Keywords: Physics | Rock Skipping | Kurt Steiner | Fluid Mechanics

The amount of scientific knowledge humanity has amassed about the universe is impressive. We understand how a solar system is formed from a vast spinning debris field, how the current atmosphere of Earth was created by microscopic cyanobacteria, and how atoms are not the smallest building blocks of nature. To reach this level of understanding, scientists have focused on the “classic” principles of energy, matter, and forces. These principles have become the foundation for how all phenomena are described within the universe. However, theoretical physicists have been unable to produce a unified theory that presents these principles in a single, coherent framework. Albert Einstein, who famously discovered that energy and matter are related by a squared constant, was working on a unified theory of forces, but left it unfinished. Currently, the quest to understand the physics of the universe is focused on experiments conducted within the Large Hadron Collider at CERN [1]. Inside this 27-kilometer particle accelerator, subatomic particles are slammed into each other at close to the speed of light, and the aftermath of these collisions are examined zeptoseconds (10-21s) after they occur [1].

In seeking answers for how the universe works, scientists continue to focus on measuring energy, matter, and forces, and have gone to great lengths to remove any “subjective” human influence on these measurements. However, this approach might be counterproductive. It is impossible to remove human influence from science because the terms of energy, matter, and forces are human-produced constructs. In addition, when scientists conduct experiments, they choose which subjects to study and how to study them. They analyze the results through a subjective human lens, which inherently involves their own consciousness. To produce a single model for the universe, a better approach might be to focus not only on describing phenomena with the “classic” principles, but to include human elements, such as perception and awareness. What if the key to finding a single model to describe the universe requires human consciousness to be included? To explain why this might be true, let’s look at the example of how world record holder Kurt Steiner uses his consciousness and perception to skip rocks.

The Energy, Matter, and Forces Present in Rock Skipping

When a stone slips across the smooth surface of a lake in the fading glow of a summer sun, the circular ripples that dance away from the stone are mesmerizing. As the stone descends onto the swarm of molecules that comprise the surface, the water responds to the stone’s kinetic energy, propelling the stone along its path. After its energy has been exhausted, the surface tension of the water breaks, and the lake swallows the small projectile. While the image of a rock skipping across a lake is simple and almost magical, the physics involved in describing this phenomenon are complex.

To start understanding the physics behind skipping rocks, it is important to consider the material properties of the matter that is being thrown. One of the most popular types of rock used for skipping is shale, a sedimentary rock that forms from silt compacting in an aquatic environment for tens of thousands of years. Eventually, erosion breaks and smooths the shale into palm-size chunks that can be used for skipping. The density of shale is between 1.19 and 1.54 ounces per cubic inch, which means that most hand-sized shale stones weigh between 4 and 7 ounces [2] [3]. What makes shale an excellent choice for rock skipping is its uniformly distributed mass. Unlike other sedimentary rocks, like conglomerate, which is comprised of irregularly shaped pebbles held together with silt, a rounded piece of shale will have its center of mass close to its geometric center. This provides a stabilizing effect that allows the shale to maintain its orientation while it spins.

After selecting a stone, a person must transfer stored energy into kinetic energy to propel the rock towards the water. Some potential energy transferred to the rock comes from the sugars stored inside the human body. Specifically, when the chemical bond holding the third phosphate in an adenosine triphosphate molecule to the other phosphate groups is broken, approximately 5.07 ×10-23 joules of energy are released [4]. This release of stored chemical energy causes the muscle fibers in the human arm to contract and move. The rock is then put into motion by electrostatic repulsion forces between the atoms in the human hand and the atoms constructing the shale. These electrostatic forces are often overlooked when people think of physical forces, but are ultimately what drive collision mechanics. As the rock is put into motion, it must also be forced to rotate. Typically, this is done by keeping the rock in rolling contact with a rigidly extended index finger. This method allows the rock’s center of mass to continue unrestrained in a linear direction, while a contact force is imparted to the edge of the rock. The resulting coupled moment between the rock’s motion and the contact force makes the rock spin. Finally, as the rock drops from the human hand toward the surface of the water, more energy is added to the rock by Earth’s gravitational field.

The Collision Between the Rock and the Water

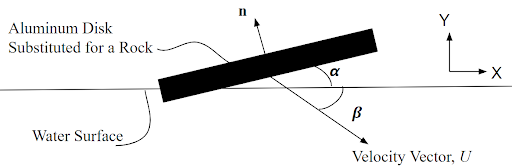

After these forces are applied to the rock and the rock has its initial kinetic energy, the rock will move in both a horizontal (X) and vertical (Y) direction towards the surface of the water. The interaction between the spinning rock and the water’s surface is complex, and scientists are still investigating the energy transfer that occurs. In one empirical study, Rossellini et al. built a model to describe the magnitude of the force imparted to a skipping rock when kinetic energy is transferred from the negative Y direction to the positive Y direction. To simplify the model, Rossellini et al. used machined aluminum disks instead of natural rocks, and assumed the following collisional configuration presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Simplified Collision Model Created by Rossellini et al. [5].

The key parameters described in the model consist of , the angle between the bottom surface of the disk and the surface of the water, , the angle between the disk’s velocity vector and the surface of the water, and U, the disk’s velocity. After launching several disks at the water, the researchers determined that for best skipping results, the time the disk was in contact with the water should be minimized. For the aluminum disk used by Rossellini et al., the collision time was minimized when was approximately 20 degrees [5] [6]. This initial angle was unchanged after the first collision with the water due to the gyroscopic stabilizing forces that were present because the disk was spinning. This meant that on each consecutive skip, the disk maintained the same angle.

When looking for a limiting factor that could determine how many skips a launched disk could achieve, Rossellini et al. found that the most important parameter was , and that decreased rapidly with each consecutive skip. Armed with this empirical data, the researchers presented the following equation that describes the motion of the disk, presented here as Equation 1,

where w is the density of the water, Swet is the surface area of the disk submerged in water, g is gravity in the negative Y direction, and n is the direction perpendicular to the surface of the disk. K is a constant that is equal to 1 when the disk is in contact with the water, and is equal to 0 when the disk is in the air. When Equation 1 is integrated with respect to time, a relationship is revealed between and the Y component of velocity U. As the Y component of velocity decreases with each skip due to dissipative frictional forces, also decreases. When the value of is close enough to 0, the water line will move over the disk and push it underwater, even if the disk still has kinetic energy in the positive X direction.

The Gap Between Theory and Reality

The work done by Rossellini et al. shows a counterintuitive aspect of rock skipping that might go unnoticed by a casual rock skipper: the vertical component of velocity matters more than the horizontal component. While most people might focus on throwing the rock out over the water horizontally, they should focus on imparting sufficient downward velocity to the rock. In other words, when the rock is thrown at the correct angle, the harder the rock is initially thrown down at the surface of the water, the farther it will skip. This insight is a great example of how scientists use the concepts of matter, energy, and forces to explain a real phenomenon occurring in the universe. However, this model also shows the limitations of using just empirical modeling to describe a phenomenon. For example, Rossellini et al.’s assumption that a machined aluminum disk is equivalent to a naturally occurring piece of shale is not true. A piece of palm-sized shale has many surface irregularities that will push and slice through the viscous water differently than a manufactured aluminum disk. To measure the precise magnitude of energy transfer between each rough nook in the weathered surface of a piece of shale and the water would be significantly more complex and cannot fully be captured with a model. Additionally, most empirical models observing rock skipping assume that energy dissipation due to frictional forces is a function of the rock’s speed before and after the collision. This modeling choice neglects the complex transfer of energy from the rock’s kinetic energy to the energy stored in the circular displacement waves on the water. It is common practice to make large assumptions like these in modeling, but these assumptions prevent a complete understanding of the phenomenon.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, scientific empirical models like the one developed by Rossellini et al. overlook the contribution of human perception in rock skipping. For instance, the process of choosing the piece of shale that is going to be skipped requires human sensory input through a visual inspection as well as a physical touch inspection. Not all pieces of shale will have the same potential for skipping, but human intuition is used to decide which rocks will work the best.

The Bridge

On September 6, 2013, a 13,000-year-old piece of Devonian shale became the focal point of a transfer of energy between a man and a body of water inside Allegheny National Forest in Pennsylvania. This transfer of energy culminated in 88 consecutive circular waves of disturbance rippling through an otherwise still lake [7]. Before this mystifying moment, the previous record for rock skipping was 65 skips. This new record was not the result of empirical models predicting a rock’s behavior. Instead, this feat was accomplished through the skill and intuition of a man named Kurt “Mountain-Man” Steiner.

Steiner’s ability to throw does not comport with the physics-based model presented by Rossellini et al. That study shows that the optimal angle for rock skipping is 20 degrees, but Steiner does not use this angle; his world record was produced by using an angle of approximately 30 degrees. There appears to be an element of Steiner’s rock skipping that science cannot explain. Perhaps Steiner’s perception and intuition help him find what “classical” physics cannot. In his words, “it’s not just [a stone’s] size, it’s not weight, it’s not thickness. It’s every little feature. You start to pick up on things over time” [8]. This explanation is vague, but it is hard to put into words the intuition Steiner has developed after devoting his life to studying the phenomenon. For over 20 years, Steiner has put his soul into perfecting stone skipping, pursuing it over his marriage and a traditional lifestyle. Since 1997, he has been living in the Pennsylvania wilderness, connecting with nature and transforming his body and mind into the perfect medium to transfer energy to a stone. Steiner has carefully examined each of the over 250,000 stones he has thrown in his life to find the right type of nooks that will help skip the rock when it makes contact with the water. It is something about Steiner’s awareness of nature and natural phenomenon, his consciousness, that enables him to skip rocks in a way scientists cannot.

Beyond Rock Skipping

Scientists are getting closer to understanding how the universe works. In 2022, the Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded to Alain Aspect, John Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger for proving that quantum entanglement cannot be explained by “hidden variables” [9]. Quantum entanglement states that two subatomic particles can be connected in such a way that when a physical property of one of the particles is observed, the same physical property of the other particle will change, even though the particles are separated by a very large distance. In other words, quantum mechanics appears to suggest that being aware of a physical property can affect change in the universe. Similarly, awareness is involved in rock skipping. It is Kurt Steiner’s awareness, or consciousness, of nature and its properties that enable him to interact with the environment and to skip stones past what seems scientifically possible. While stone skipping might seem like a bizarre place to look for the key to understanding how the universe works, it might not be so strange after all. In their quest to produce a model that explains how the universe works, perhaps scientists should focus on developing an approach that captures the type of human awareness that enables Steiner to skip a rock in a way science cannot explain. Whether it is human perception, intuition, or consciousness, the human element in understanding the universe cannot be ignored.

So, the next time you are standing on the edge of a quiet body of water, pick up a rock. Examine how the old shale feels in your hand in the last zeptoseconds before you release it. And think about how your ability to skip a stone across a body of water might be the conduit to understanding the inner workings of the universe.

Citations:

[1] “The Large Hadron Collider.” CERN, home.cern/science/accelerators/large-hadron-collider. Accessed 7 Mar. 2024.

[2] E. Vitz, et al. “Density of Rocks and Soils.” Chemistry LibreTexts, Libretexts, 14 Mar. 2023, chem.libretexts.org/Ancillary_Materials/Exemplars_and_Case_Studies/Exemplars/Geology/Density_of_Rocks_and_Soils.

[3] R. Buchanan. 2010, Kansas Geology: An Introduction to Landscapes, Rocks, Minerals, and Fossils (2nd ed.): Lawrence, Kansas, University Press of Kansas, 240 p.

[4] D. Jacob. “Physiology, Adenosine Triphosphate.” StatPearls, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 13 Feb. 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553175/#:~:text=Through%20metabolic%20processes%2C%20ATP%20becomes,fuel%20the%20ever%2Dworking%20cell.

[5] L. Rosellini, F. Hersen, C. Clanet, and L. Bocquet. “Skipping Stones,” Journal of Fluid Mechanics, vol. 543, no. 1, pp. 137–146, 2005, doi: 10.1017/S0022112005006373.

[6] C. Clanet, F. Hersen, and L. Bocquet. “Secrets of successful stone-skipping,” Nature, vol. 427, 29 (2004).

[7] K. Steiner. “Stone Skipper.” YouTube, YouTube, www.youtube.com/channel/UCu5CsDxNhQGquwrZc8bCLGQ. Accessed 7 Mar. 2024.

[8] S. Williams. “Stone Skipping Is a Lost Art. Kurt Steiner Wants the World to Find It.” Outside Online, 20 Sept. 2022, www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/water-activities/stone-skipping-kurt-steiner/.

[9] Caltech’s Faculty. “What Is Entanglement and Why Is It Important?” Caltech Science Exchange, scienceexchange.caltech.edu/topics/quantum-science-explained/entanglement. Accessed 7 Mar. 2024.